“Industry was King, and dirty rivers were a sign of prosperity.” – John Hartig

For over 100 years, the Chicago River was treated as the city’s waste dump.

Throughout the 19th and much of the 20th century, pollution from industrial plants, sewage and trash from the growing population, and animal blood and entrails from stock yards were all dumped into a river once known for its abundance of wild onions growing along the banks. Following those centuries of growth and abuse, the original wetland system was unrecognizable. No one would want to be eating anything that managed to grow alongside the Chicago River when the river’s flow was reversed in 1900.

The reversal by itself was a monumental feat of engineering designed to protect the city’s main water source, Lake Michigan, from the waste and pollutants in the river. However, although Chicago’s politicians and engineers argued that the reversal of the river would resolve the river’s waste problem, time proved otherwise. In 1911, eleven years after the flow was reversed, the Chicago Daily Times published photographs of a man and a chicken standing on the surface of Bubbly Creek, where the stock yards dumped their waste.

But now, a century after a chicken took a walk on the river’s surface, about 500 swimmers intentionally jumped into the Chicago River’s still-a-little-murky waters to prove a point: the once-abused Chicago River can be reclaimed. The days of a casual swim, free of water quality checks and official sign-offs, may yet be a ways off, but not such a ways off.

Local action

Behind September’s swim are years of advocacy by local Chicago players. One of those, a non-profit called Friends of the River, has been fighting for the Chicago river since 1979. From so-called “guerilla” canoeing to annual trash removal days and development plans, Friends of the River has helped turn the river from a polluted wasteland into the valued resource it always could have been.

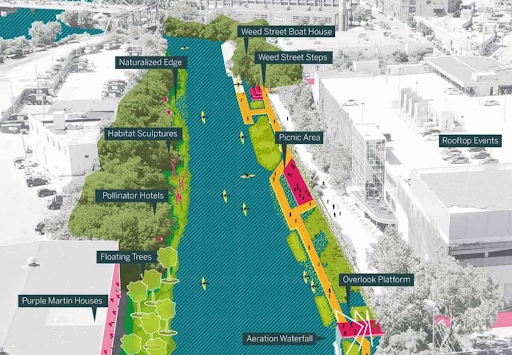

Another prominent Chicago group is Urban Rivers, a nonprofit focused on transforming Chicago’s waterways into wildlife sanctuaries. One of the results of their efforts is the Wild Mile, the world’s first floating urban ecopark, located across from Goose Island in the North Branch Canal. The Wild Mile aims to recreate a natural wetland habitat through a “wildlife-first” approach, while also connecting people with nature through public access to a variety of spaces. As a work in progress, the Wild Mile currently reaches 700 linear feet, with plans to continue to expand to a full mile as funding allows.

As the world’s first floating eco-park, the Wild Mile is creating a new method of combining wildlife-first habitat restoration with public access on urban waterways. The floating structures are planted with native Illinois wetland species to provide aboveground habitats. The wetland plants then grow underwater root structures, providing resources for fish, freshwater mussels, and other species that no longer have viable habitats in the urbanized river.

Why care so much about a river, anyway?

Amidst immigration protests and threats of authoritarianism from the federal government, food insecurity, and budget concerns, the river might not seem all that important. And it is true that Chicago has many other things on its mind.

But looking through the Wild Mile designs put together by the City of Chicago in collaboration with Urban Rivers and other community partners, one gets a sense of what the river could be. Picture the river the north side of Chicago could have if we put enough attention, planning, and funding into it.

Planned area of the completed Wild Mile outlined in dotted white line. Image from https://wildmile.org/history

Images from the Wild Mile Framework Vision.

In addition to providing much-needed habitat to local wildlife, the project plan includes spaces for recreation, art, food, and performance. Even while the project is in progress, the existing portions are open to the public, serving as a space for interacting with nature, hosting educational visits, and attending other events led by Urban Rivers.

Green spaces like the Wild Mile serve a real benefit. In addition to improving mental and physical well-being, they also provide a source of economic growth. In the United States, local parks and recreation agencies alone generated almost $218 billion in economic activity in 2019 and supported over 1.2 million jobs.

There are hidden benefits of the WIld Mile too. Along the restored riverbed are mussels placed by Urban Rivers, each one filtering between 8 and 15 gallons per day. The plants also act as a method of filtration, as their root systems pull up pollutants like heavy metals from the water and sequester them.

By supporting projects like the Wild Mile, we are not just beautifying the river. Above water, the full Wild Mile, when completed, will be a place for community, nature, and economic growth. All the while, more wildlife and vegetation are below the surface filtering the water, making it an ever safer and cleaner resource for all — human, turtle, beaver, and otherwise — who live in and around the Chicago River.

Visit the river of the future

The Wild Mile might not be completed, but that does not mean you can’t enjoy the progress that has been made. Visit Chicago’s floating eco-park year-round, any time of day. Get involved in volunteer programs run by Urban Rivers and Friends of the River, on and off the river. Or, learn more about the history of the Chicago River at Friends of the Chicago River’s McCormick Bridgehouse & Chicago River Museum.

The Chicago River may only be the city’s second-best water feature, but it may be the best reflection of the city’s history. As Chicago continues to manage its relationship between urbanization, nature, and impact on the planet, the Chicago River and its ongoing restoration should be a sign of hope. Maybe by the time the 2026 Chicago River Swim rolls around, more than 500 swimmers might want to jump in.

Reader Question:

What is your perception of the Chicago River? What would it take for the river to be seen as fully ‘restored’?